Error correcting a miscalibrated sensor

As you may know from my last post, I used to have a Winsen MH-Z19B CO2 sensor. In fact, I have 4 of them now, since after my little incident I was left with 0. Hopefully I’ll keep these ones alive.

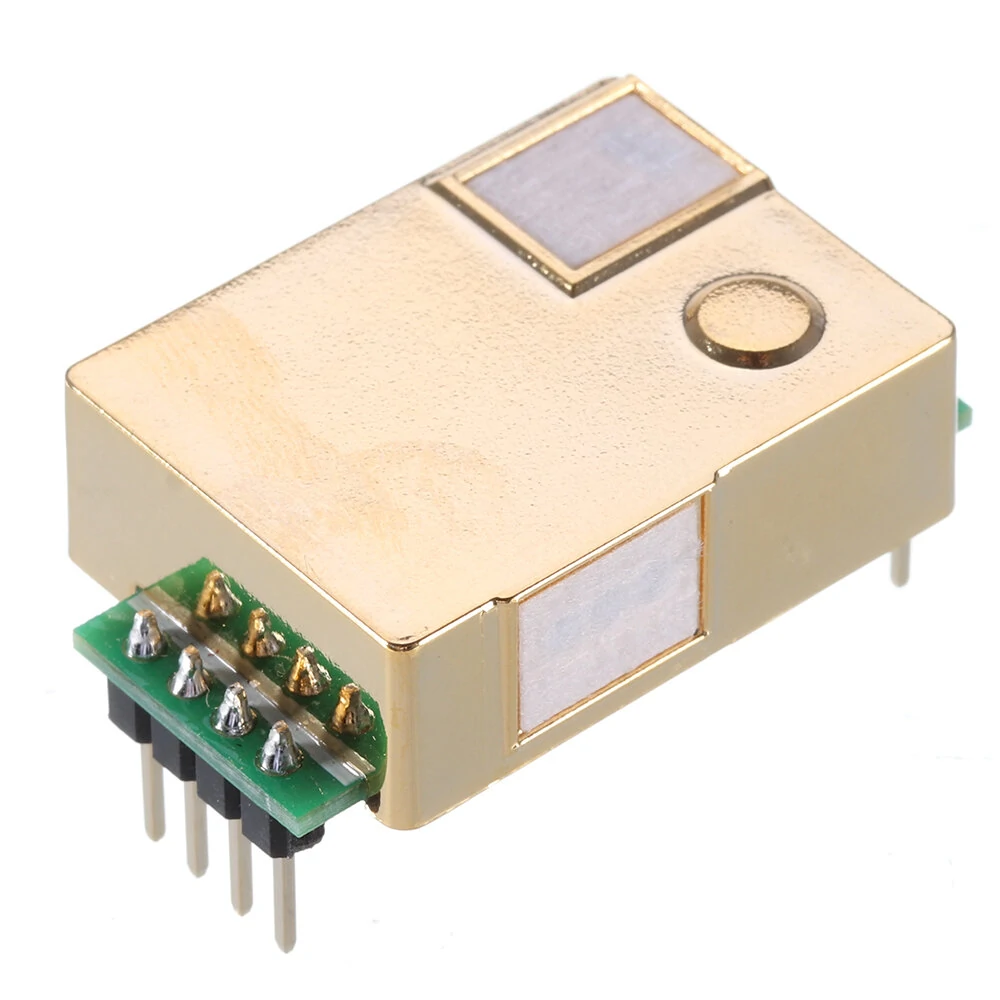

As a refresher, this is a CO2 sensor that uses NDIR (non-dispersive infrared) to detect the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere. Every 6 seconds, it performs a measurement, and in order to do so it needs a relatively accurate temperature measurement. This is because the measurement method for CO2 used is generating some heat, causing far infrared radiation to be emitted through black-body radiation, which is then bounced around a chamber and measured by an IR sensor, which is much like one in a thermal imaging camera or a motion sensor.

First attempt: Univariate linear functions

The particular sensor I got (and broke) was off in its temperature measurement

by about 6 Kelvin. This meant that all its measurements were off by a certain

amount (according to my Temtop P1000 air quality measurement station). So

naturally, my first idea was to assume (hope?) that the error is a linear

factor, maybe with an additional offset, and if I could just compute the

function f(x) = mx + b, I could easily correct the measurement it gave me. A

line can be described by 2 points, so I would just need 2 measurements and have

my function. Unfortunately, my measurements are pretty inaccurate, because CO2

concentration constantly changes, especially when I’m in the room, turning O2

and food into CO2. So the next step was to turn to least-squares optimisation.

- Collect a bunch of data points: (CO2 according to my sensor, CO2 according to Temtop reference sensor)

- Optimise a linear function to have the least amount of error given all the data points.

The Temtop also has the same sensor in it, so I figured it would be easy to match them up.

Of course, storing a bunch of data points as well as the code for computing

least squares and also having to run that code on startup sounded like a really

bad idea to me and my 8KB of program memory. Fortunately, there’s constexpr,

the promise that C++ can be executed at compile time.

Unfortunately, however, since I was using C++11, and a rather old version of

AVR-GCC (5.x), I could only really use single return statement constexpr. This

resulted in a rather convoluted implementation of least-squares for one variable

(see for yourself).

The problem of temperature

The solution worked perfectly. Or so I thought.

Since I had been doing all my measurements in my room at a pleasant 294-295 Kelvin, my corrective function worked perfectly inside that temperature range, but became wildly wrong at lower temperatures like the less pleasant 288 Kelvin that my room would have after opening the window for a bit. Clearly, the error was not linear in one variable - it was at least two! I had to consider temperature.

The sad news here is that in order to do multivariate linear optimisation, you

basically need matrix operations like multiplication, determinant, and inverse.

Writing that in C++11 constexpr would prove to be a massive pain. Not

impossible, mind you, and I have done the kind of crazy template

metaprogramming required for this in the distant past, but I’d really prefer to

keep that past distant. So I had no choice but to try and upgrade my compiler.

It took me a while, but it turned out to be

possible

to upgrade the AVR-GCC to a more reasonable version like 7.3.0, which nicely

supports C++14 constexpr where you can basically run any

global-side-effect-free code at compile time (woohoo!).

Multivariate least squares

The final solution, which ended up actually working pretty decently, is based

around a small constexpr

matrix library

I wrote, and an algorithm from

Wikipedia.

It is now

used

to correctly return CO2 values that agree with my reference sensor.

Is this solution correct? I don’t know. The temperature sensor inside is probably a thermistor, which has a logarithmic sensitivity curve.

It’s possible that the function seems linear only in the narrow range I measured things in (much like how Earth looks flat (no, I’m not going to hyperlink to flat earthers here) when looking at a narrow slice of its surface), but is actually logarithmic in a wider range. If that’s the case, the problem is pretty easy to solve still, even with the ordinary least-squares method. I’d just make the logarithm of a value one of the variables and compute its weight. In fact, I could do that right now to see whether the function is in fact logarithmic, but for the temperature range that’s relevant to me, the function is linear enough and now I’ll move on to the next thing :).